Were the CIA Actually the Greatest Patrons, Critiques & Sponsors of 20th Century Art — or Something Deeply More Significant?

By Sam Stafford

Published 30th August 2016: 00:30 GMT

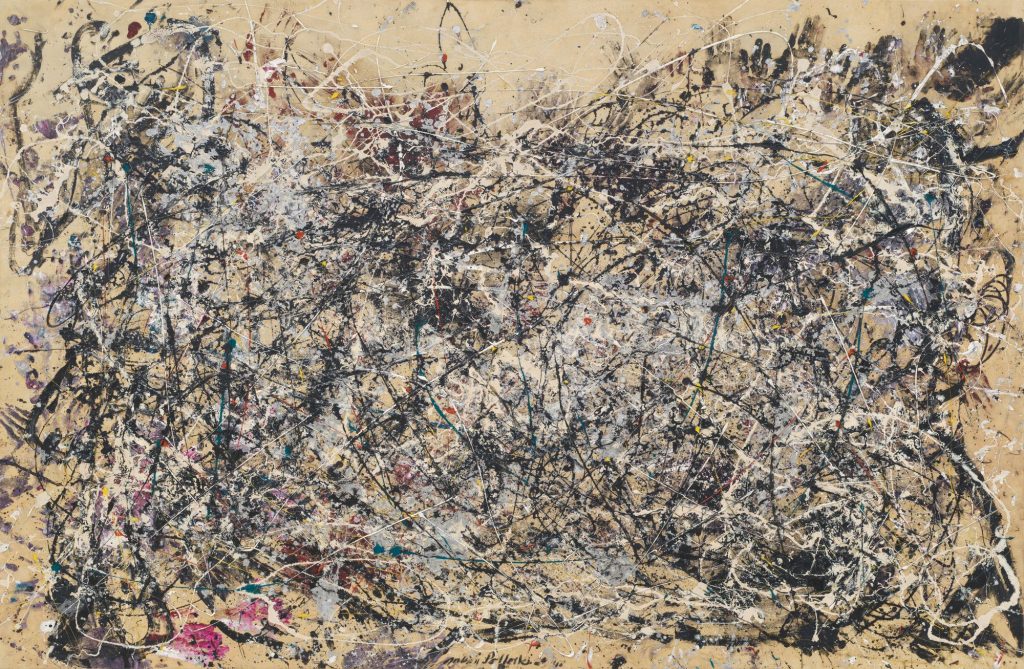

Jackson Pollock, “Number 1A, 1948.” © Metropolitan Museum of Art — Public Domain / Open Access (CC0).

There are moments in history when truth hides not behind smoke and mirrors—but behind the brushstrokes of a canvas.

In the hush of postwar galleries, under the sterile lights of Parisian museums, and between the splattered layers of paint by Jackson Pollock, a quiet, almost poetic conspiracy unfolded. It is a story that fuses power and paint, statecraft and aesthetic rebellion—a narrative so audacious it seems almost mythic. And yet, it is not myth.

It is fact.

The Shadow Patron Emerges

For centuries, emperors, popes, and kings financed the arts with marble-solid certainty: they wanted their portraits glorified, their triumphs eternalized, their power beautified. But what transpired in the mid-20th century was unlike any previous patronage in human history. It was not crowned heads or cathedral treasuries that secretly underwrote a cultural revolution.

It was an intelligence agency.

Between the hush of diplomatic corridors and the flickering projectors of Cold War strategy rooms, the Central Intelligence Agency became—almost surreally—the most discreet and determined art benefactor of the century. It wasn’t about decoration. It was about ideological artillery.

The Paris Shock

Autumn 1955. At the Musée National d’Art Moderne in Paris, a new artistic force erupted like a burst dam: Abstract Expressionism. Viewers stared at the works of Pollock, Willem de Kooning, Mark Rothko, and Arshile Gorky—and did not know whether to laugh, weep, or revolt.

What they didn’t know was that behind this avalanche of paint, dripping and pooling in reckless, elegant rebellion, stood a meticulous, calculating network of cultural engineers. The CIA was not content to fight the Soviet Union with armies and speeches alone. It would fight with ideas.

A Silent Rivalry: Paris vs. New York

Musée National d’Art Moderne, Paris, 1950s. Wikimedia Commons — Public Domain

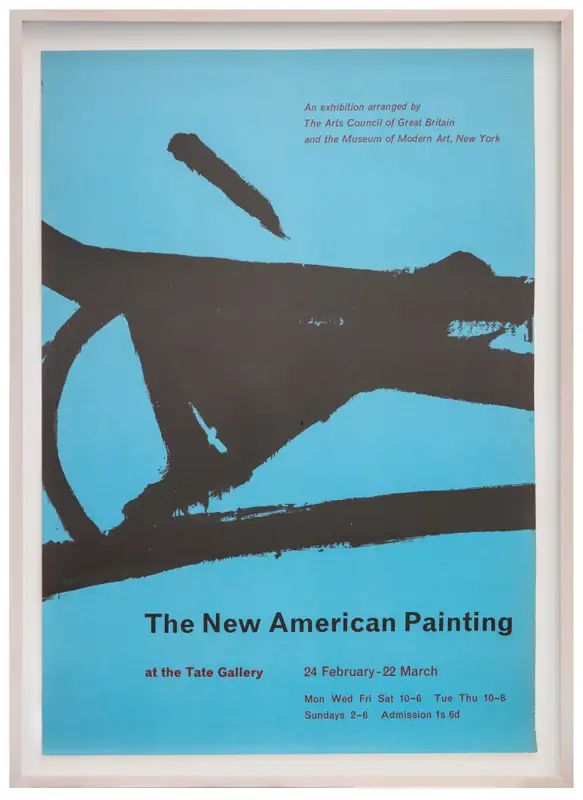

Poster for “The New American Painting” exhibition, 1958. Wikimedia Commons — Public Domain.

The battle for cultural hegemony after 1945 was fought not only in Berlin and Washington but between the ateliers of Paris and the lofts of New York. For centuries, Paris had been the unchallenged capital of high art.

By 1958, the exhibition “The New American Painting” swept across Europe like a storm. This was not just an art tour. It was a declaration of artistic independence—New York dethroning Paris, Pollock replacing Picasso as the face of the avant-garde.

The world began to believe what the covert patrons had hoped it would: that American modernism wasn’t just art; it was destiny.

Magazines, Money, and Masterminds

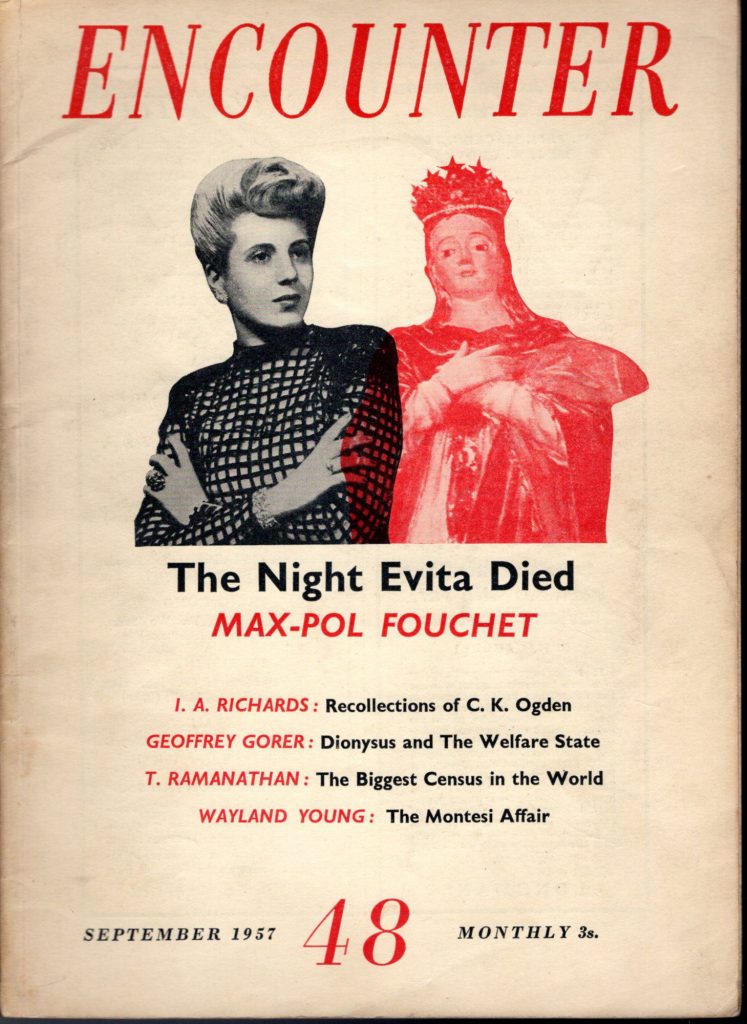

Encounter magazine cover, 1950s. Wikimedia Commons — Public Domain.

The CIA’s masterpiece was not just in exhibitions but in narrative control. Through the Congress for Cultural Freedom—an intellectual phalanx funded covertly by Washington—the agency shaped global discourse.

It funded journals like Encounter in London, Der Monat in Germany, and Preuves in France, which subtly elevated American cultural values while engaging Europe’s brightest minds. Behind every printed page, beneath every glowing critique of American art, the agency’s fingerprints were faint but present.

The Critic Who Crowned a Movement

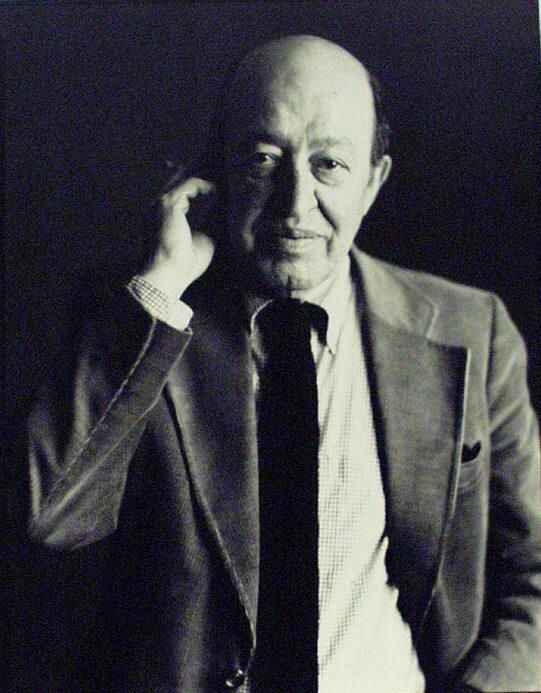

Clement Greenberg, influential art critic. Wikimedia Commons — Public Domain

Image Credits: All images are in the public domain or released under CC0 / Open Access. Sources include Metropolitan Museum of Art, Library of Congress, Central Intelligence Agency archives, and Wikimedia Commons.

No cultural revolution is complete without a prophet. Enter Clement Greenberg—art critic, Trotskyist-turned-cultural powerbroker. Greenberg’s essays did more than interpret Pollock’s work; they enthroned it.

To read Greenberg was to be persuaded that Abstract Expressionism wasn’t just art—it was the inevitable future of art. His critical authority, amplified through CIA-funded publications and galleries that courted his approval, became the invisible scepter that anointed a movement.

Legacy of a Hidden Revolution

History has a habit of romanticizing art and vilifying espionage. But sometimes, as the Cold War revealed, the two are entwined like threads in a single tapestry.

The CIA’s covert cultural war didn’t corrupt Abstract Expressionism—it accelerated its global reach. It ensured that when people thought of artistic modernity, they thought of Manhattan lofts, not Moscow collectives.

And so, in the contest between totalitarian order and creative chaos, Pollock’s brush became mightier than the sword.

Epilogue: Beyond Patronage

Perhaps the most haunting irony of all is this: Michelangelo had the Medici. Bernini had the papacy. Pollock, unknowingly, had Langley.

Unlike royal patrons, the CIA did not dictate the content of the art. It merely placed the right canvases in the right rooms before the right eyes. It understood, with clinical clarity, something that artists themselves often forget: art moves nations.

And in that strange marriage between espionage and expression, between dripping paint and geopolitical might, the world’s artistic axis tilted forever.

“The CIA didn’t paint the canvases. It didn’t shape the lines. But it did set the stage on which a new cultural empire was born.”