The Alchemy of Our Age: Inside the Global Race to Recycle the World’s Batteries

By Lola Foresight

Publication Date: 18 February 2019 — 10:39 GMT

(Image Credit: Wikipedia)

- The Hidden Weight of the Digital Age

We do not think about batteries.

We think about phones, cars, watches, drones, tablets, bikes, and the invisible machinery of a modern life humming quietly around us. But we do not think about the lithium, nickel, cobalt, aluminum, graphite and manganese — scattered across the Earth, dug up at extraordinary cost, refined in industrial crucibles, packed into the cells that animate our digital existence.

We do not think about the mines in Congo where cobalt extraction reaches into the earth with both industrial machines and human hands, including, at times, the hands of children.

We do not think about the salt flats of Bolivia where brine pools shimmer in unnatural colours, leaving ecological scars that will take generations to heal.

We do not think about the vast industrial corridors of South Korea, Japan and China where cells are assembled in immaculate production lines, then shipped across oceans to become the unseen organs of our devices.

We rarely ask: What happens when these batteries die?

For most of the 2010s, the answer was brutal.

They were buried, incinerated, shredded without care, or sent abroad to informal recycling hubs where toxic fumes curled into the sky.

It was a silent catastrophe — a mountain of discarded cells growing faster than regulators, manufacturers, or the public could comprehend.

But in late 2018, something changed.

A series of breakthroughs — in hydrometallurgy, direct cathode recycling, solid-state recovery, solvent neutralisation, closed-loop extraction — began circulating in scientific journals and at industry conferences.

The narrative shifted from inevitability to possibility.

A month later, by February 2019, one thing had become clear:

Battery recycling was no longer a niche industrial afterthought.

It was the next frontier of global sustainability.

- The Metallurgical Revolution Nobody Saw Coming

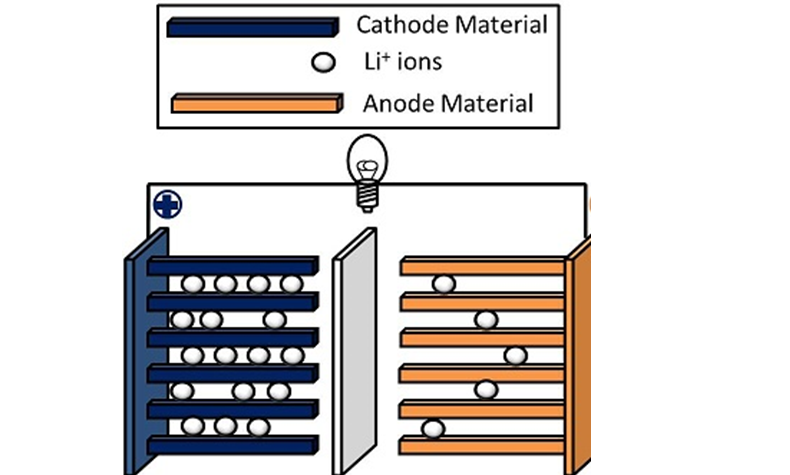

The problem with lithium-ion batteries is that they are engineered for performance, not disassembly.

Electrodes are glued, fused, layered in complex chemistries.

Separators melt or tear.

Electrolytes are volatile.

Cells swell, crack, and ignite if mishandled.

Recycling them is, in essence, an act of industrial surgery.

But researchers made a structural breakthrough: the ability to extract valuable metals at high purity without destroying their crystalline structure.

Rather than melting everything into a homogenous sludge (the crude early approach), new hydrometallurgical techniques use selective leaching agents — mild acids, organic solvents, optimised pH gradients — to dissolve specific metals while leaving others intact.

This allowed something extraordinary:

Batteries could be recycled not into raw metals, but into ready-to-use cathode materials.

Nickel-manganese-cobalt (NMC) cathodes could be stripped, purified and rebuilt.

Lithium could be recovered at far higher yields than previously thought.

Cobalt extraction no longer required high-temperature furnaces.

Graphite — long considered unrecoverable — could be reclaimed with purity approaching that of virgin material.

Recycling stopped being destruction.

It became recovery.

It became renewal.

For the first time in industrial history, we were learning how to unmake, remake, and reuse the most complex chemical engines of the information age.

III. The Race to Close the Loop

By early 2019, a global race had begun.

In North America, start-ups in Nevada, California, and Ontario began building pilot plants capable of recycling tens of thousands of tonnes per year.

Their promise was bold: domestic supply chains independent of geopolitical risk.

In Europe, Germany and Sweden led an engineering renaissance, exploring automated disassembly lines where robots dismantled packs energy-free.

They imagined a continent where EV batteries lived multiple lifetimes — first in cars, then in stationary storage, then as repurposed cells in micro-grids, and finally as high-value recovered materials feeding back into gigafactories.

In Asia, China — already a battery giant — accelerated even further.

State-backed recycling quotas, buy-back mandates, and vertically integrated systems meant that for the first time, recycling became a strategic industry, not an afterthought.

Entire megacities became nodes in a new circular economy: materials left the ground once, and never returned to it.

The ambition was unprecedented:

**A world where lithium-ion batteries would never again be “waste.”

Only feedstock. Only future. Only possibility.**

- The Materials That Hold Civilisations Together

To understand why battery recycling matters, we must understand what batteries are made of.

Their chemistries are not trivial mixtures; they are the skeletal metals of modern civilisation.

- Lithium — the lightest metal, essential for charge balance

- Nickel — boosting energy density

- Cobalt — stabilising layered structures (though ethically fraught)

- Manganese — lowering cost and improving safety

- Graphite — one of the most energy-intensive materials to produce

- Copper, aluminum, steel — the structural bones

As electric vehicles skyrocketed, so did the demand for these elements.

Forecasts were grim: shortages of nickel by mid-2020s, lithium bottlenecks, cobalt supply issues.

Without intervention, energy transitions could have become new engines of exploitation.

Recycling changed the equation.

Materials once bound for landfills became strategic reserves.

Each battery pack became a future mine — urban mining on a planetary scale.

And in the process, recycling became an ethical project:

a chance to reduce mining in fragile ecosystems, to alleviate the burden placed on communities near extraction sites, to rewrite the moral geometry of the green revolution.

- The Chemistry of Resurrection

A recycled battery material is not a degraded material.

It can be better.

Recycled NMC cathodes often show improved cycling stability.

Recycled graphite can be reconditioned to higher operational purity.

Recycled lithium carbonate can reach pharmaceutical-grade refinement.

This is the quiet alchemy of our era:

turning old batteries not into lesser parts, but into equal or superior versions of themselves.

It is unlike any recycling revolution before it.

Paper becomes weaker; plastic becomes brittle; glass becomes cloudy.

Batteries, however, can be reborn without losing identity or capability.

It is not recycling.

It is reincarnation.

- Fire, Water, and the Art of Dismantling a Storm

The dangers remain.

A swollen lithium-ion cell is a coiled storm.

Puncture it and flames blossom at 1,000°C — metal fire, unquenchable.

Flood it with water and the chemical reaction intensifies.

Recycling plants must operate like surgical theatres.

Fire-suppression systems.

Negative-pressure chambers.

Robotic pre-sorting lines.

Cryogenic freezing to disable unstable cells.

Acoustic sensors listening for micro-cracks.

Inert-atmosphere glove boxes.

This is recycling as high science.

A fusion of metallurgy, robotics, chemical engineering, mineralogy, and environmental design.

VII. The Circular Future

Imagine a world in which:

- An EV battery lives 12 years

- Then powers a neighbourhood micro-grid for another decade

- Then becomes backup storage for hospitals or data centres

- Then, cell by cell, is disassembled

- Its metals reintegrated into a new EV battery

- And the cycle repeats

This is the “closed-loop ecosystem” that researchers now envision — a world where energy storage is not linear but cyclical.

In such a world, mining decreases.

Pollution drops.

Supply chains stabilise.

Geopolitical tensions ease.

Cost of batteries falls.

Electric vehicles become more affordable.

Grid storage becomes ubiquitous.

Renewables scale exponentially.

And the world’s transition to clean energy accelerates.

VIII. The Ethical Imperative

Battery recycling is not just innovation.

It is necessity.

Climate models require a massive shift to renewables, which require storage, which require batteries, which require materials.

But materials are finite.

Their extraction carries immense human and ecological cost.

To recycle a battery is to reduce mining.

To reduce mining is to reduce suffering.

To reduce suffering is to make the energy transition morally coherent.

This is where technological optimism collides with human rights.

A clean energy future cannot be built on the backs of exploited populations.

Recycling is the bridge between ambition and justice.

- The Economics of a New Age

A decade ago, battery recycling was a money-losing enterprise.

Today, it is a multibillion-dollar sector.

As battery packs grow larger (EVs), as regulations tighten (EU), as material prices rise (nickel, lithium), recycling becomes economically irresistible.

Investors — once cautious — now view recycling as the next semiconductor boom.

Governments view it as strategic independence.

Manufacturers view it as risk reduction.

Consumers will come to view it as ethical responsibility.

And as yield rates climb above 90%, recycling becomes not a cost center but a competitive advantage.

- The Coming Era of Battery Stewardship

By February 2019, the world had awakened to a truth:

batteries are no longer disposable.

They are infrastructure.

The next decade will bring:

- Battery passports (full lifecycle traceability)

- Mandatory recycling quotas

- Second-life certification standards

- Regional recycling hubs

- Carbon accounting for materials

- Trade policies built around circularity

The age of extractive consumption is ending.

The age of material stewardship is beginning.

- The Alchemy Becomes Culture

We live in a civilisation built on invisible miracles — electricity, semiconductors, satellites, fibre optics — and now the miracle of closed-loop electrochemical systems.

Recycling batteries is not glamorous.

It does not have the sleek elegance of a smartphone or the futuristic aura of autonomous vehicles.

But it is the infrastructure that underwrites both.

It is the unseen work that allows the seen world to flourish.

And like all great revolutions, its significance will be understood most fully in retrospect — when future generations look back and marvel that, for a time, we threw modern gold into the landfill.

You May also like

By Lola Foresight