National Memorial for Peace and Justice, Montgomery, Alabama

By Rojina Bohora

Publication date: 10 May 2018, 09:00 GMT

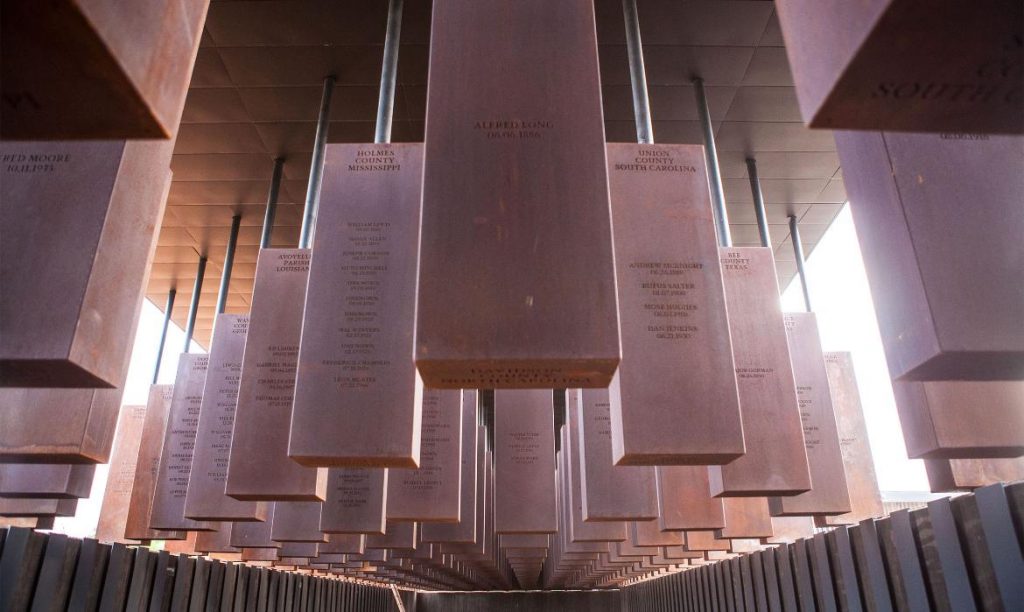

(Image credit: National Memorial for Peace and Justice, Montgomery — Architecture by MASS Design Group. Photograph via Wikimedia Commons, licensed under Creative Commons Attribution–ShareAlike 4.0 [CC BY-SA 4.0]).

Architecture That Refuses Consolation: Space, Weight, and the Work of Moral Memory

I.A Memorial That Withholds Comfort

Most memorials are designed to console.

They offer resolution, closure, a sense that grief has been acknowledged and therefore contained. Architecture smooths the edges of trauma, translating violence into abstraction so that visitors may leave reassured — saddened, perhaps, but unburdened.

The National Memorial for Peace and Justice does not do this.

Opened in Montgomery in April 2018, the memorial withholds comfort deliberately. It does not reconcile. It does not redeem. It does not resolve. Instead, it insists on presence — on standing with history rather than passing through it.

This is architecture that refuses to perform healing prematurely.

II.The Ground on Which the Memorial Stands

Montgomery is not incidental to this project. It is structural.

The city was once a major hub of the domestic slave trade. It later became a symbolic centre of the Civil Rights Movement. These histories are often narrated separately — one as origin, the other as redemption.

The memorial rejects that narrative separation.

By situating itself on a hill overlooking the city, the memorial establishes a physical and moral relationship to the landscape of American racial history. Visitors do not arrive accidentally. They ascend.

The climb is gentle, but intentional. It prepares the body for confrontation rather than spectacle.

III. The Weight of Names

The memorial’s primary architectural elements are 800 weathering-steel columns, each representing a county in the United States where documented lynchings occurred. Engraved on each column are the names of victims — more than 4,400 — along with dates and locations.

Names here are not illustrative.

They are structural load.

The columns begin at eye level and gradually rise overhead as visitors move through the space. What begins as encounter becomes enclosure. What can initially be read becomes harder to see. Bodies that once stood upright now hang.

The architecture does not depict violence.

It reproduces its spatial logic.

IV.Suspension as Spatial Ethics

As the path descends, the steel columns lift fully off the ground. They hover. They loom. They no longer share the visitor’s plane.

This suspension is the memorial’s most devastating architectural decision.

Hanging bodies are not referenced metaphorically. They are made spatially unavoidable. The visitor does not observe from a distance; they pass beneath.

The experience is quiet. There is no sound design, no didactic narration, no aesthetic cushioning. The steel absorbs light. The air feels heavier.

Architecture here does not explain injustice.

It places it above you.

V.Weathering Steel and the Refusal of Purity

The choice of weathering steel is critical.

Unlike polished stone or bronze, the material oxidises. It stains. It changes with time. It leaves residue on the ground below.

This is not maintenance failure. It is intent.

The memorial insists that racial violence is not safely contained in the past. It continues to mark the present. The material enacts that continuity physically.

There is no pristine surface to admire.

There is only endurance.

VI.The Duplicate Columns: Memory as Obligation

Beyond the suspended columns, the memorial grounds a second set of identical steel monuments. These are intended to be claimed by counties represented above and installed locally.

This gesture transforms remembrance into responsibility.

Memory is no longer centralised. It is distributed. Each county must decide whether to confront its own history publicly or leave the column unclaimed — a visible absence.

The memorial thus extends beyond its site. It becomes a network, a challenge, a test of civic courage.

Architecture here is not complete at opening.

It demands continuation.

VII. Against the Aesthetics of Distance

Many memorials rely on abstraction to make trauma palatable. The National Memorial for Peace and Justice does the opposite.

There are no figures.

No allegorical forms.

No interpretive murals.

Only names, dates, places — arranged in a spatial sequence that denies detachment.

The architecture does not allow the visitor to aestheticise suffering. It denies the comfort of interpretation and insists on confrontation.

This refusal is ethical.

VIII. Silence as Design Choice

The memorial is notably quiet. There is no soundtrack, no programmed narration, no curated emotional arc.

Silence here is not absence. It is space for reckoning.

Visitors move slowly. Many stop. Some weep. Others stand motionless. The architecture does not guide response.

This restraint is rare — and powerful.

It recognises that grief, particularly racial grief, cannot be standardised.

IX.The Role of MASS Design Group

MASS Design Group’s work has long focused on architecture as a vehicle for social justice rather than aesthetic assertion. At Montgomery, this ethos reaches its most distilled form.

The architects do not foreground authorship. There is no signature gesture. The building’s force comes from alignment — between form, history, material, and intent.

The memorial does not belong to its designers.

It belongs to the names it carries.

X.Memorial as Civic Mirror

The National Memorial for Peace and Justice does not function as a destination alone. It functions as a mirror held up to American civic life.

The question it asks is not “Do you remember?”

It is “What will you do with what you know?”

By tying memory to geography, by naming counties rather than abstractions, the memorial collapses distance between violence and the present-day institutions that emerged from it.

History is not elsewhere.

It is here.

XI.Architecture That Refuses Closure

There is no final moment of release in the memorial. No culminating vista that resolves the experience.

Visitors exit carrying weight rather than relief.

This is deliberate.

The memorial understands that closure, in this context, is a lie — one that allows injustice to be archived rather than addressed.

Architecture here does not complete mourning.

It sustains it.

XII. The Ethics of Witness

To walk through the memorial is to be implicated.

You cannot move quickly without noticing your own haste.

You cannot remain neutral without recognising your position.

The architecture does not accuse.

It reveals.

Witness becomes an active state rather than a passive one.

XIII. Conclusion: A Space That Will Not Let You Go

The National Memorial for Peace and Justice is not designed to be revisited casually. It does not invite leisure. It does not soften with familiarity.

It remains difficult.

And that difficulty is its integrity.

In a culture that often rushes toward reconciliation without truth, this memorial insists on something more demanding: endurance without forgetting.

It stands not as a monument to the past, but as an ongoing architectural demand — that memory be carried, not consumed; that justice be pursued, not commemorated away.

This is architecture that does not console.

It holds.

You May also like

Guoco Tower (Tanjong Pagar Centre), Singapore

By Rojina Bohora

By Rojina Bohora

By Rojina Bohora