Can We See A Great Future or, To Be A Touch Buddhist — An Even Greater Present

By Verdina Sea

Publication Date 11th December 2025: 12:56 GMT

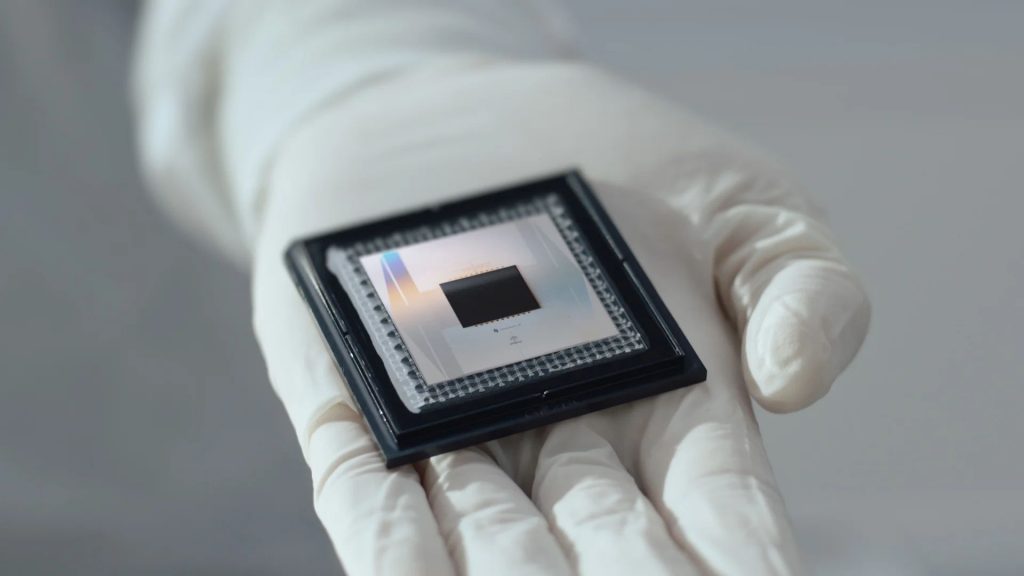

(Image Credit: Engineering @ Meta)

Imagine this.

You’re standing in your kitchen in 2033, staring at the kettle.

You blink twice — not hard, just your normal “I’m mildly bored” blink.

A tiny pattern in that blink, plus an almost imperceptible flutter of muscles in your forearm, plus a shift in the electrical fog around your auditory cortex (measured quietly by your earbuds), is enough for your personal AI to conclude:

“Tea. Now. Earl Grey. And please don’t talk to me about emails while the water boils.”

On your eyes: clear contact lenses that look totally normal.

On your wrist: a slim band that feels like jewellery.

In your ears: something that looks like regular earbuds.

To everyone else, you just look… dressed.

To the system, however, you are a walking, breathing, non-invasive BCI.

And the wild part?

The “neural contact lens” everyone keeps whispering about is only one tile in this mosaic.

Let’s unpack, step by step, how we plausibly get there by 2030–2035 — and why the lens itself is far less magical, and far more mundane, than you might think.

Step 1 — Realising the “BCI” Has Already Left the Lab

Fifteen years ago, “brain–computer interface” meant:

•gel in your hair,

•32–64 electrodes under a scuba-diving cap,

•a PhD student muttering about artefacts.

Today, non-invasive BCI has quietly migrated into lifestyle hardware:

•EEG in headbands, earbuds, and around-the-ear flexible arrays.

•fNIRS in lightweight forehead or hairband modules.

•EMG in wristbands that read subtle muscle activity and map it to clicks, drags, swipes, and shortcuts.

•Eye tracking and attention estimates baked into AR/VR headsets.

The crucial pivot is conceptual:

The “BCI” is no longer a single device.

It’s a constellation of sensors — brain-adjacent, muscle-adjacent, eye-adjacent — all fused by AI.

This is the first clue to understanding why a “neural contact lens” in the 2030s will not stand alone as some telepathic crystal disc.

It will be the ocular node of a much bigger, body-scale interface.

Step 2 — Meta-Style Smart Glasses as the Dry Run

Next, look at what Meta and others are doing with smart glasses.

They’re not just sticking a camera in a frame and calling it a day. They’re quietly assembling:

•Cameras that see what you see.

•Microphones that hear what you hear.

•Tiny displays that put text and icons directly in your field of view.

•Neural input devices (wrist EMG, eye-based gestures, voice) that let you command AI without obvious movement.

Think of these glasses as version 0.9 of the neural ecosystem:

•The frame handles power, processing, radios, and AI models.

•The glasses know context (where you are, what you’re looking at, who’s speaking).

•The paired wristband and ear-devices know what your body is intending to do.

Right now, the display sits in the lens of the glasses.

From an engineering point of view, migrating that display into a contact lens is evolution, not revolution:

•The infrastructure — AI, compute, wireless, multimodal sensing — is already living in the glasses and the phone.

•The contact lens doesn’t need to be smart enough to run GPT; it just needs to be smart enough to show you something and feel some things.

Glasses are, in other words, the training wheels for the neural contact lens era.

Step 3 — Quietly Stuffing Electronics into Your Eye (Safely)

While social media obsesses over VR headsets, ophthalmology labs have been doing something quietly radical:

They’ve been putting electronics into contact lenses and proving that:

•You can embed sensors that measure intraocular pressure (for glaucoma).

•You can power them wirelessly with tiny inductive loops.

•You can print stretchable circuits and strain gauges onto soft, oxygen-permeable materials.

•You can, in some cases, add micro-LEDs or optical elements that create simple heads-up displays.

Some prototypes already show:

•Real-time pressure readouts.

•On-lens drug reservoirs that release medication in response to what the sensors see.

•Experimental AR elements — simple symbols, icons, and eventually small text or overlays.

At this stage, the contact lens is a biomedical gadget:

•It senses the eye.

•It talks wirelessly to an external device (a phone, glasses frame, or pendant).

•It sometimes acts on the eye (drug release, visual cues).

Crucially, it is not reading your cortex.

It’s reading your eye — and your eye, while emotionally influential, is not a direct portal into your thoughts.

Which brings us to the next important realisation.

Step 4 — Accepting That Your Cornea Is Not a Mind-Reading Surface

A lot of sci-fi illustrations make it look like:

“Put some nano-electrodes on the cornea and boom, instant telepathy.”

The physics is less romantic:

•Brain signals are created inside your skull.

•They diffuse through brain tissue, cerebrospinal fluid, skull, and scalp.

•By the time they reach the outside world, they’re faint, smeared, and messy. That’s what EEG deals with.

Your cornea and lens, meanwhile, are sitting at the front of the eyeball, not magically inside your cortex. They can give you:

•Eye movement signals (where you’re looking).

•Corneal strain (eye pressure, blink force).

•Tear composition (some metabolic and stress markers).

•Retinal response signatures.

All useful. None of it is “here is your decoded inner monologue in high definition.”

So if we’re honest and serious:

A “neural contact lens” will never be the main brain-reading device.

It will be an exquisitely intimate display and ocular-sensing surface, plugged into a broader neural system.

Once you accept that, the design becomes much more elegant — and much more plausible by 2030–2035.

Step 5 — Building the Neural Mesh Around the Body

Let’s now assemble the full system as it might reasonably exist in the 2030s.

5.1 The ear: listening to your cortex

In your ears, or wrapped discreetly around them, sit:

•Soft, flexible EEG electrodes.

•Tiny infrared sources and detectors (for superficial hemodynamics in the temporal cortex).

•Inertial sensors and mics.

They don’t read your every thought, but they track useful states:

•Are you focused or drifting?

•Are you drowsy, overloaded, or relaxed?

•Did you just orient strongly toward a sound or visual object?

5.2 The wrist: listening to your intent

On your wrist:

•High-resolution EMG electrodes monitor the tiny electrical signals that travel to your fingers and hand.

•AI models recognise patterns like:

•“Pinch to click”

•“Swipe to scroll”

•“Hold to select”

•Or even continuous cursor-like motion mapped from your imagined finger movement.

This becomes your silent vocabulary of commands, with no need to wave your arms around like you’re directing traffic.

5.3 The lens: talking to your eye and feeling it talk back

On your eye:

•A smart contact lens carries:

•A micro-LED or diffractive display panel.

•One or two ultra-low-power chips for control, power management, and basic sensing.

•Sensors for tear chemistry, corneal strain, maybe tiny electrodes for eye-motion pattern detection.

It’s powered wirelessly (no battery in your eye).

All the heavy AI lives in your phone, your glasses frame, or a necklace hub.

The lens continuously answers two questions for the system:

1.“What exactly is this person seeing right now?”

(Because it controls some of the photons reaching your fovea.)

2.“How is this person’s eye behaving and feeling?”

(Are you straining, blinking more, showing signs of fatigue, dryness, stress?)

Step 6 — Letting AI Tie the Whole Thing Together

Now imagine the AI layer that orchestrates this mesh.

It has:

•Context from cameras and microphones (what’s around you).

•Neural-adjacent data from your ears (broad cognitive state).

•Intent signals from your wrist (what you want to do).

•Ocular and health data from your lenses (how you’re coping).

From this, it can:

•Adapt what it shows you in the lens.

•If you’re overloaded, it simplifies the UI.

•If you’re bored, it surfaces richer information.

•If you fixate on a word or object, it knows you care and can offer more.

•Adapt when it interrupts you.

•If your neural and ocular signatures scream “deep focus,” it holds notifications.

•If you’re drifting, it might gently suggest a break or a change of task.

•Adapt how you interact.

•It learns personal EMG patterns at your wrist so that your “click” is unique to you.

•It refines its models of your attention, stress, and preference based on long-term data, locally tuned.

Importantly: this is not one single gadget.

It’s a networked, AI-mediated BCI ecosystem — with the contact lens as the most intimate showpiece, not the brains of the operation.

By 2030–2035 this is not crazy sci-fi. It’s a plausible extension of:

•Today’s smart glasses and AR displays.

•Today’s wearable EEG and EMG devices.

•Today’s smart medical lenses.

•Today’s on-device AI.

The science is incremental, but the experience would feel radically new.

Step 7 — The Price of Intimacy: Data, Agency, and… Eyeballs

Of course, to get there, we have to swallow some fairly intense pills:

•Biocompatibility and safety:

•Can we really wear electronics-loaded lenses for 12–16 hours a day without wrecking our corneas?

•What are the long-term consequences of chronic RF powering right next to our eye tissue?

•Neuro-privacy and manipulation:

•Once a system knows your attention patterns, stress signals, and visual preferences in exquisite detail, the line between “helpful assistant” and “hyper-targeted persuasion engine” gets very thin.

•Neuro-rights scholars are already arguing that mental privacy and cognitive liberty should be treated like new human rights, not optional settings.

•Dependence and identity:

•When your everyday perceptions and actions are co-curated by a neural mesh, where exactly do you end and the system begins?

•How does it feel to take the lenses out and be “just you” again, in raw, un-augmented reality?

These aren’t side notes. They’re central to whether society accepts neural contact lenses as mundane tools or treats them as the new cigarettes: glamorous, addictive, and increasingly regulated.

Step 8 — The Reveal: What a “Neural Contact Lens” Actually Is

If you were hoping for a single magical disc that reads your thoughts and blasts holo-ads onto the inside of your skull, the truth is both less cinematic and more profound.

By 2030–2035, a realistic “neural contact lens” is:

•A highly miniaturised AR display and ocular-sensing surface,

•Wirelessly powered and networked,

•Paired with:

•ear-EEG and/or hemodynamic sensors near your skull,

•EMG on your wrist for precise, silent commands,

•cameras and mics in nearby devices for context,

•and an AI stack that fuses everything into an adaptive, personal interface.

It doesn’t “read your mind” in the mystical sense.

It coaxes, queries, and collaborates with your mind, through a choreography of light, muscle twitches, bioelectric hum, and context-aware guesswork.

The lens is not the wizard.

It’s the wand-tip.

And Yet…

After all of that — the neuroscience, the optics, the nanofabrication, the AI, the ethics — we arrive at a very human question:

You, in 2033, rubbing your slightly dry eyes at the end of a long day.

Do you really want your eyeballs to be part of this network?

Because if we’re being sincere, given the pace of existing trends, a first generation of this ecosystem — clunky, expensive, but real — is likely within touching distance of 2030–2035.

Which leaves us with the only honest final line:

But even though that’s only 5 to 10 years away, who on earth would actually want that, and whatever for, surely we are better off going to buy a pair of Meta’s righ

You May also like