By Rojina Bohora

Publication date: 10 May 2018, 09:00 GMT

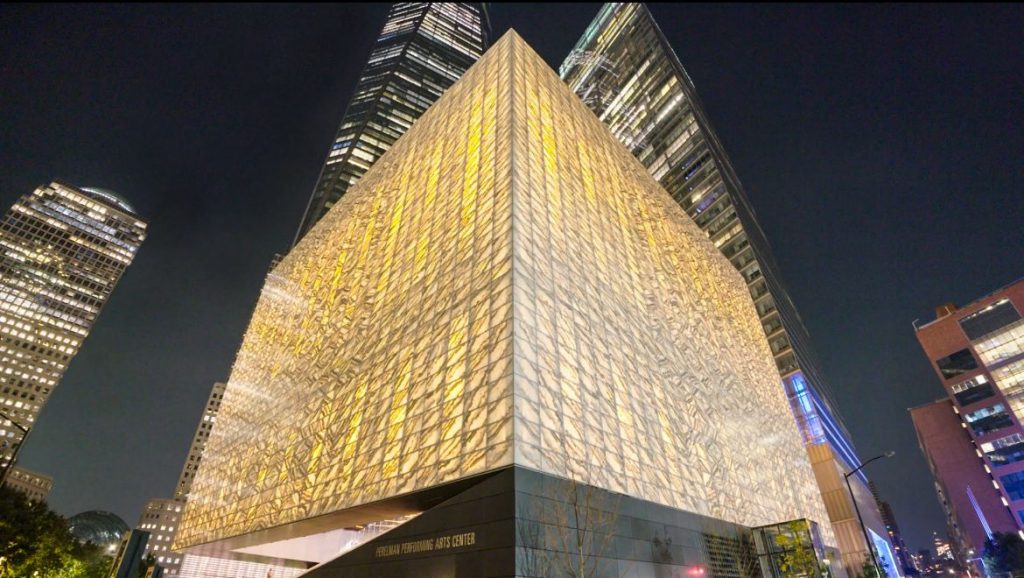

(Image credit: Burrell Collection Extension, Glasgow — Architecture by John McAslan + Partners. Photograph via Wikimedia Commons, licensed under Creative Commons Attribution–ShareAlike 4.0 [CC BY-SA 4.0]).

Light Returned: How a Museum Learned to Breathe Again

I.The Rare Privilege of Getting It Right the Second Time

Few modern museums are given the chance to be reconsidered rather than replaced.

The Burrell Collection, opened in 1983 within Pollok Country Park, was always admired for its sensitivity to landscape and daylight — yet over time, its promise dimmed. Leaking roofs, environmental instability, and compromised galleries threatened both the building and the collection it housed.

The extension and refurbishment completed in March 2022 did not seek reinvention.

It sought restoration of intent.

II.A Museum Born From Landscape

From the outset, the Burrell Collection was conceived as an inhabitable edge between art and nature — a low-slung structure embedded within parkland rather than rising above it.

John McAslan + Partners approached the extension not as a contrast, but as continuation. The building’s original horizontality, timber rhythm, and porous relationship with the landscape were treated as non-negotiable principles.

This was not about updating a style.

It was about recovering clarity.

III. Light as Moral Responsibility

The museum’s greatest architectural failure was also its greatest aspiration: daylight.

Over time, glazing systems degraded, solar control failed, and artworks were increasingly placed at risk. Many institutions would have responded by retreating into darkness.

The Burrell extension does the opposite.

New lightwells, upgraded roof systems, and refined glazing reintroduce daylight as disciplined presence, not uncontrolled spectacle. Light becomes legible again — filtered, directional, and calm.

The museum does not fear light.

It masters it.

IV.Environmental Control Without Withdrawal

One of the project’s most impressive achievements lies in reconciling conservation standards with openness.

Temperature and humidity are stabilised without sealing the building from its surroundings. Views to Pollok Park remain intact. Seasonal change remains perceptible.

The museum does not choose between preservation and experience.

It insists on both.

V.Circulation Rewritten, Not Replaced

Internally, circulation has been clarified rather than dramatically altered.

Routes are intuitive. Sightlines extend. Bottlenecks dissolve. Visitors move without confusion or fatigue — a subtle but transformative shift.

The architecture does not impose narrative.

It supports discovery.

This restraint allows the collection — famously eclectic in origin and chronology — to retain its idiosyncratic richness.

VI.Timber, Stone, and Continuity

Materially, the extension remains faithful.

Timber detailing echoes the original building’s warmth. Stone floors ground the experience physically and metaphorically. New insertions are contemporary but deferential — precise without being assertive.

Nothing announces itself unnecessarily.

The building understands that its authority comes from consistency, not contrast.

VII. A Collection That Defies Categorisation

Sir William Burrell’s collection resists curatorial neatness — medieval tapestries beside Chinese ceramics, Gothic sculpture alongside Impressionist painting.

The renewed architecture embraces this complexity.

Galleries vary in scale and mood. Transitions are gradual. No single spatial language dominates. The building adapts itself to the collection, not the reverse.

VIII. Accessibility as Architectural Ethic

The refurbishment significantly improves accessibility — physically, cognitively, and socially.

Entrances are clearer. Routes are equitable. Spaces accommodate diverse modes of engagement.

This is not accessibility as compliance.

It is accessibility as design principle.

The museum opens itself to more people without diluting its seriousness.

IX.Sustainability Without Self-Congratulation

The project delivers major environmental improvements — energy efficiency, material longevity, and lifecycle performance — yet never advertises its virtue.

There are no performative gestures. No visible eco-symbols.

Sustainability here is treated as professional obligation, not architectural identity.

X.A Public Building That Trusts the Public

Perhaps the most significant quality of the renewed Burrell Collection is its trust.

It trusts visitors with daylight.

It trusts art with space.

It trusts architecture with restraint.

In an age of over-curation and institutional anxiety, this trust feels quietly radical.

XI.Glasgow’s Long Memory

The Burrell Collection occupies a particular place in Glasgow’s cultural consciousness — generous, civic, and slightly eccentric.

The extension honours this character.

It does not transform the museum into international spectacle. It reinforces its role as local treasure with global depth.

XII. Conclusion: When Repair Becomes Revelation

The Burrell Collection extension demonstrates that architectural excellence does not always lie in novelty.

Sometimes it lies in listening again — to original ideas, to landscape, to light, to use.

By restoring daylight, clarifying movement, and stabilising environment without retreat, the project allows the museum to become what it was always meant to be.

Not louder.

Not newer.

But whole again.

You May also like

By Rojina Bohora

By Rojina Bohora

By Rojina Bohora