Grand Egyptian Museum, Giza

By Rojina Bohora

Publication date: 8th January 2024; 09:13 GMT

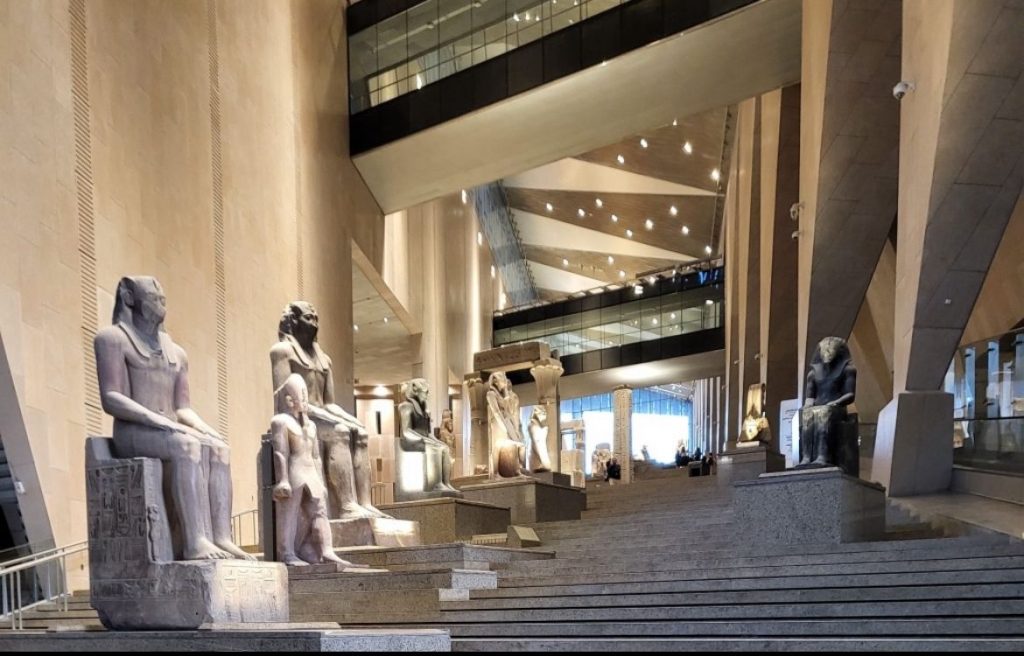

(Image credit: Grand Egyptian Museum, Giza — Architecture by Heneghan Peng Architects. Photograph via Wikimedia Commons, licensed under Creative Commons Attribution–ShareAlike 4.0 [CC BY-SA 4.0]).

Between Pyramid and Present: How a Museum Learned to Hold Time

I.The Weight of Proximity

Few buildings begin with a burden as heavy as the Grand Egyptian Museum.

Set at the edge of the Giza Plateau, within sight of the pyramids, the museum confronts an architectural paradox: how to present antiquity without competing with it; how to frame the past without turning it into spectacle.

The answer offered by Heneghan Peng Architects is neither mimicry nor monumental rivalry. It is alignment.

The museum does not attempt to rival the pyramids’ permanence.

It accepts their authority — and works in their shadow.

II.A Building Drawn From Geometry, Not Iconography

From a distance, the museum reads as a precise, angular form, its massing aligned carefully to the pyramids themselves. Sightlines are calibrated so that ancient monuments remain visually dominant, even as visitors approach a vast contemporary institution.

This alignment is not symbolic flourish.

It is geometric discipline.

The building positions itself as mediator — orienting visitors physically and intellectually toward the plateau, rather than away from it.

III. Stone That Is Not Stone

The museum’s façade appears monolithic, yet it is composed of translucent stone panels that filter light rather than block it.

This material choice is crucial.

Rather than replicating ancient masonry, the façade refracts desert light, allowing the building to glow softly by day and become lantern-like by dusk. Solidity is suggested, not imposed.

The museum looks ancient without pretending to be old.

IV.The Atrium as Threshold, Not Hall

At the heart of the museum lies a vast atrium — often described in terms of scale, but more accurately understood as threshold.

Visitors do not enter a gallery immediately. They enter a space of orientation, where light, geometry, and monumental artifacts prepare the mind for temporal shift.

The atrium slows the body.

It signals that this is not a place of consumption, but of transition.

V.The Long Stair and the Act of Ascent

One of the museum’s most defining elements is its monumental staircase, ascending gradually toward the galleries while framing views of the pyramids beyond.

This ascent is not theatrical.

It is deliberate.

Movement upward becomes metaphorical without becoming didactic — a progression from contemporary ground toward accumulated history, from immediacy toward duration.

The architecture does not explain history.

It positions the visitor to receive it.

VI.Galleries Without Drama

Inside, the museum avoids the darkness and compression typical of artifact-heavy institutions.

Galleries are generous, legible, and evenly lit. Objects are given space — physically and intellectually — to be encountered without sensory overload.

This restraint reflects a confidence often absent from blockbuster museums.

The architecture trusts the artifacts.

VII. Tutankhamun and the Refusal of Spectacle

Housing the complete collection from Tutankhamun’s tomb is an unprecedented curatorial task — one that could easily have tipped into spectacle.

The museum resists this temptation.

Rather than isolating the collection as singular event, it integrates it into a broader narrative of continuity. Tutankhamun becomes part of a lineage, not an exception.

This curatorial humility is architectural as much as museological.

VIII. Climate, Conservation, and Control

The museum’s environmental systems are designed with conservation rather than visitor comfort as first principle.

Light levels are carefully managed. Temperature and humidity are controlled with redundancy. Circulation routes minimise dust intrusion from the surrounding desert.

None of this is visible.

And that is the point.

The building serves the artifacts, not the other way around.

IX.The Museum as National Gesture Without Nationalism

As a state-backed institution, the Grand Egyptian Museum could easily have drifted into architectural nationalism.

It does not.

There are no triumphalist axes, no symbolic crowns, no forced narratives of resurgence. The building speaks in a calm register — confident without being declarative.

National pride here is expressed through care, not proclamation.

X.Contemporary Egypt Without Erasure

Importantly, the museum does not pretend that Egypt ended in antiquity.

Its approach routes, public spaces, and scale acknowledge the modern city around it. The building is contemporary in its construction, its logistics, and its public ambition.

It presents antiquity without freezing the present.

XI.Time as the Primary Material

What distinguishes the Grand Egyptian Museum is not its size — though it is immense — but its handling of time.

The building stretches time rather than compressing it. It asks visitors to slow, to adjust scale, to accept duration.

In an era of accelerated consumption, this is quietly radical.

XII. Conclusion: Holding History Without Grasping It

The Grand Egyptian Museum succeeds because it understands its own limitations.

It does not attempt to replace the pyramids.

It does not attempt to summarise Egypt.

It does not attempt to astonish through form alone.

Instead, it offers a framework — spatial, intellectual, and emotional — in which history can be encountered without distortion.

Between the desert and the city, between antiquity and now, the museum holds a careful line.

It does not claim eternity.

It respects it.

You May also like

By Rojina Bohora

By Rojina Bohora

By Rojina Bohora