New Historic Findings On One Of The Few Privately Owned Michelangelo Paintings Left In The World

By Art Editor in Chief Carolina Berghinz with Valeria Berghinz & Ginevra Berghinz

Publication date 1st August 2021: 06:00 GMT

Anne Lipscomb – Editor in Chief’s “Pick of the Year”

Michelangelo’s Lost Pietà & The Secrets That Survived the Inquisition

In July 2021, a scholarly report signed by Prof. Antonio Macchia quietly left the Pontificio Istituto Orientale. It looked like any other academic paper — modest in design, polite in tone. But its contents?

A cultural earthquake.

It documented with archival proofs, scientific analysis such as carbon dating, and Renaissance correspondence the existence — and survival — of one of the only privately owned paintings by Michelangelo Buonarroti:

The Pietà di Roma

A work long whispered about, partially documented, at times confused and even occasionally doubted until now.

With the publication of this report, a puzzle 450 years old finally unlocks itself publicly for the fist time, revealing:

– two nearly identical Pietà paintings, made by Michelangelo between 1543–46

– one owned by Vittoria Colonna, one by Cardinal Reginald Pole

– their concealment during the persecution of the Spirituali

– their disappearance after the Council of Trent

– and finally, the reappearance of one — the Pietà di Roma — within a noble Neapolitan family whose records reach back to the early 1800s.

What follows is the first public, fully coherent account of this rediscovery — exclusive & to BeYouandTea

Put the kettle on and prepare yourself for a story of genius, secrecy, danger, devotion, and survival.

Part I — Rome in Turmoil: The Birth of a Hidden Masterpiece

The Sack of Rome (1527): The End of Renaissance Light

Editorial image: “Il Sacco di Roma,” Lanzichenecchi mocking the Church in Rome’s burning streets.

The Sack of Rome was not merely a military catastrophe — it was a theological and existential rupture. Artists who had once glorified human perfection suddenly confronted destruction, sin, and the fragility of grace. Out of this broken world emerged a movement obsessed with salvation, conscience, and the soul:

The Spirituali

Led by: Cardinal Reginald Pole, English noble, near-Pope, mystic thinker

Portrait of Cardinal Reginald Pole Saint. Petersburg – Hermitage Museum (Image Credit: Wikipedia)

Vittoria Colonna, aristocrat, poet, and the intellectual flame who converted Michelangelo from a public artist into a spiritual one

Marcantonio Flaminio, author of Il Beneficio di Cristo

Theologians who believed salvation flowed from grace, not works — ideas dangerously close to Protestantism.

Their informal home: Viterbo

Their danger: the Roman Inquisition.

These thinkers were not reformers. They were seekers — and Michelangelo became one of them.

Part II — Michelangelo the Mystic

Vittoria Colonna: The Woman Who Changed Michelangelo

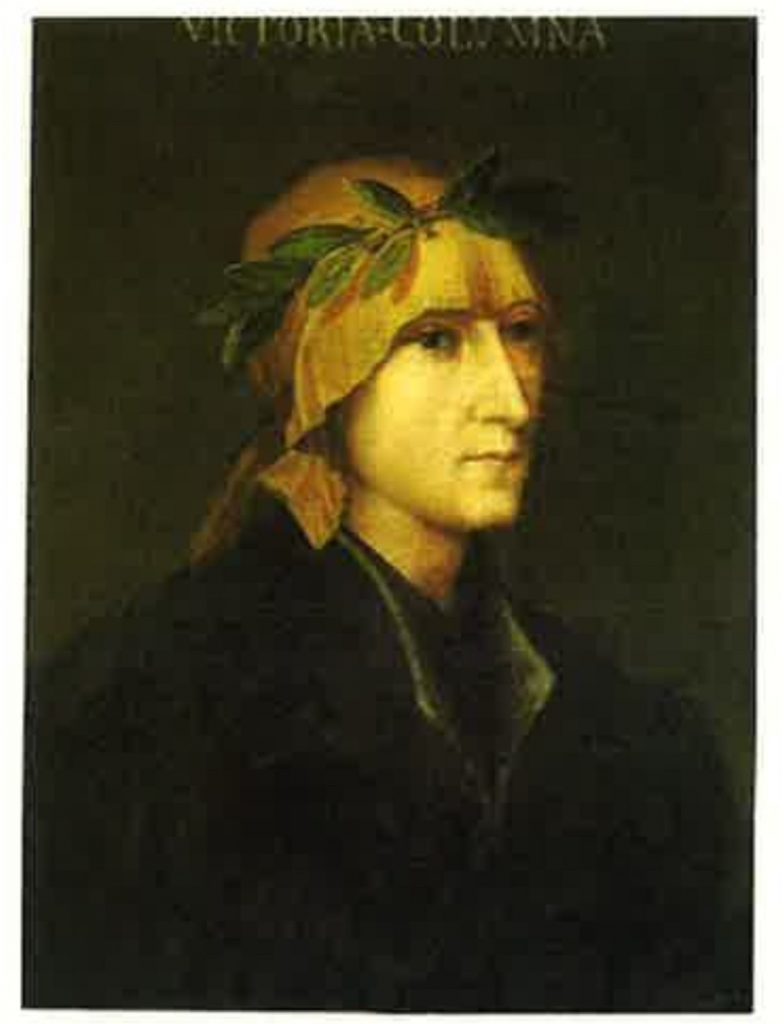

Portrait of Vittoria Colonna in her late life Rome – Colonna Family Collection

When Michelangelo met Vittoria Colonna around 1538–39, he was in his sixties —

a man already immortal in marble, but restless in spirit.

She awakened in him a new dimension: a hunger for interiority, for grace, for a Christ not as divine judge but as suffering humanity. Under her influence he produced a series of small wooden devotional paintings — intimate, contemplative, meant for private meditation.

Foremost among them: a Pietà, created expressly for her.

Part III — The Explosive Letters (1543–1546)

The First Bombshell: Two Pietàs

The correspondence between Bishop Pietro Bertano and Cardinal Ercole Gonzaga (Mantua State Archives) reveals not rumor but fact:

Two versions of the Pietà existed by May 1546

Both were by Michelangelo

One was owned by Vittoria Colonna

The second was owned by Cardinal Reginald Pole

Pole took his version with him to the Council of Trent

He insisted the painting’s existence remain secret

Because possession could condemn him under the Inquisition

This is not speculation.

This is documentary confirmation.

Why secrecy?

Because after 1546, the doctrines of the Spirituali were officially condemned. Possessing their imagery — especially works linked to Michelangelo — became dangerous. Michelangelo himself risked being implicated.

Thus:

He himself had every reason to hide the existence of these paintings.

And he succeeded.

For centuries.

Part IV — Why the Paintings Vanished for 450 Years

Michelangelo was the most celebrated artist of his age — yet even he bowed before the iron hierarchy of 16th-century society. Artists depended on nobles. The Spirituali were becoming heretics. The Inquisition was watching.

And so: the Crucifixion sent to Tommaso de’ Cavalieri remained with his family, silent

the Pietà given to Vittoria Colonna disappeared into monastic custody after her death in 1547. Cardinal Pole fled the Council of Trent. Spirituali members were executed, (e.g., Pietro Carnesecchi, 1567)

spiritually dangerous artworks were hidden, renamed, misattributed, or forgotten

This is why neither Pietà resurfaced in documented history until modern scholarship.

Part V — The Reappearance: The Pietà di Roma

An Heirloom Hidden in Plain Sight. The trail reopens in Naples, February 18, 1814, in a notarized testament by Prince Giovan Battista Dentice di Frasso bequeaths to his nephew:

“A painting by Michelangelo Buonarroti on a wooden board.”

This document this is written is real. It is still owned by the Dentice family. Subsequent findings reveal:

The painting had belonged earlier to Monsignor Francesco Dentice (1728–1804), a member of the papal household of Benedict XIV and later Governor of the Sabina province — the very region bordering Viterbo, spiritual homeland of the Spirituali.

The Dentice family preserved the painting without ever imagining it could be Michelangelo — it was simply a treasured devotional heirloom.

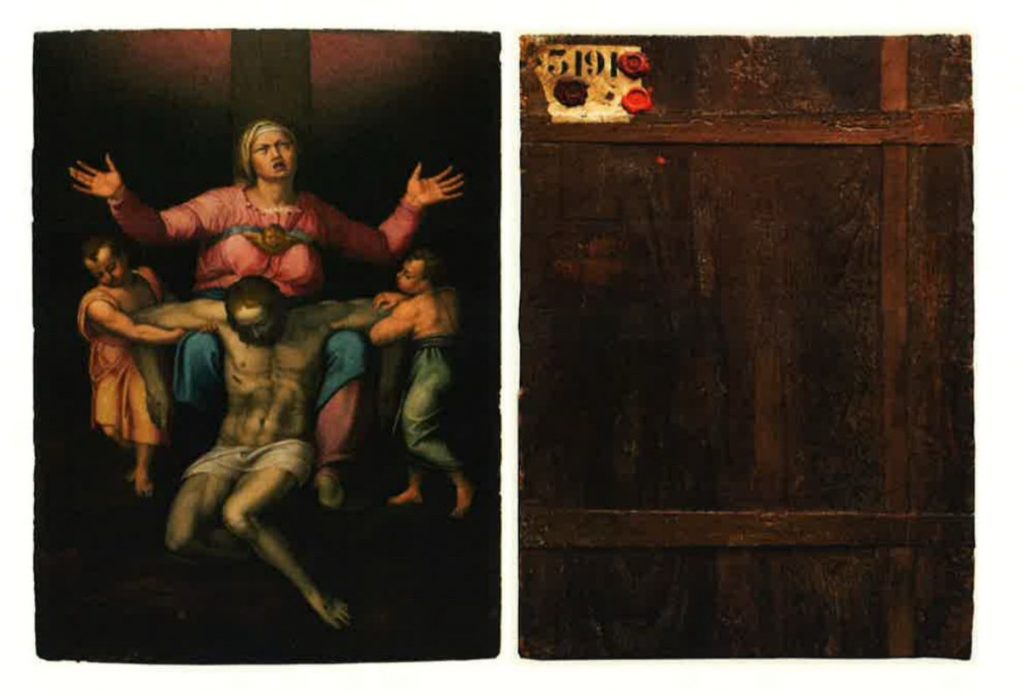

Editorial image: Pietà di Roma (front and reverse) with the wooden table and seals.

The back bears:

multi-generational wax seals

inventory number 3191

structural features consistent with 16th-century panel construction

A domestic relic — not a trophy.

Part VI — The Scientific Proofs

Between 2013 and 2014, the Pietà di Roma underwent a battery of scientific tests:

C14 carbon dating of the wood,X-ray imaging & reflectographic analysis

material studies at ENEA laboratories (Rome & Casaccia)

All confirmed:

The panel dates to the first half of the 16th century.

The work is not an 18th-century copy.

The underdrawing corresponds to Michelangelo’s known hand.

Further corroboration:

The lanette degli Angeli of the Sistine Chapel show striking compositional similarities

The preparatory drawings match sketches preserved at the Louvre in Paris and British Museum in London

The format, size, and structure correspond to descriptions in 16th-century letters

This all culminated into an historic milestone:

Part VII — Official Recognition

June 30, 2012 — Declared of High Historical and Artistic Interest as The Italian Ministry of Cultural Heritage classified the painting as:

“of considerable historical and artistic interest”

Whilst placing a restriction on its international movement.

This is not done for minor works.

This is the treatment reserved for national treasures.

June 28, 2016 — Prof. Heinrich Pfiffer’s Verdict

Prof. Pfiffer, one of the world’s leading experts on the Sistine Chapel and a scholar at the Pontificia Università Gregoriana:

affirmed the painting is by Michelangelo

and validatedthe stylistic and technical coherence with Michelangelo’s late devotional work

By July 2021, the scholar’s consensus was no longer reserved— it was affirmative.

Michelangelo’s Pietà survived.

And it lives today in the private collection of Count Andrea de’ Reguardati, also known to hold contemporary masterpieces by the likes of another Italian artist Omero Tarquini

Epilogue — The Resurrection of a Masterpiece

Four and a half centuries ago, Michelangelo painted a Pietà so intimate, so theologically daring, that its very existence became dangerous.

It was hidden, protected, nearly erased

yet protected again, unknowingly, by a noble Neapolitan family who kept it precisely because it was sacred.

And now?

Because of letters in Mantua, wax seals in Naples, chemical isotopes in Casaccia, and the scholarship of Prof. Macchia, Pfiffer, and others — we know the truth: the Pietà di Roma is almost certainly an original Michelangelo.

A survivor.

A relic of forbidden theology.

A whisper of the Spirituali, frozen in paint.

A masterpiece painted not for popes or kings — but for the soul of a woman who inspired Michelangelo to imagine Christ not as judge, but as human.

This is not merely new art history.

This is the rediscovery of a lost piece of Michelangelo’s heart.