The Oldest Continual Peace & Alliance Treaty or Something Far, Far Greater

By Rose Polipe

Publication 1st November 2025 08:08 GMT

In a world of shifting allegiances and ephemeral alliances, there stands one diplomatic relationship that has outlived empires, monarchies, revolutions, and world wars. It has endured not centuries, but nearly a millennium of political tempests: the alliance between Portugal and United Kingdom.

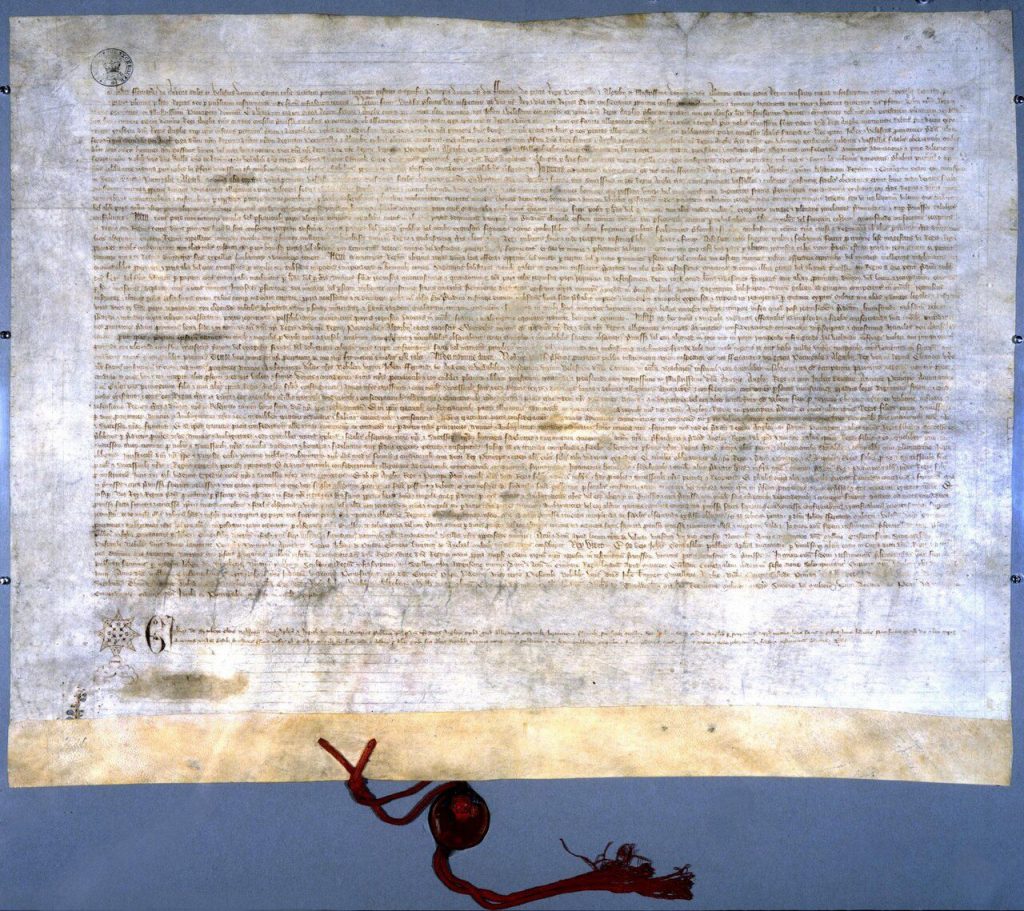

Forged in 1373 through the Anglo-Portuguese Treaty of 1373 and reaffirmed by the Treaty of Windsor (1386), this pact represents the oldest still-active diplomatic alliance in human history. But to merely call it an “alliance” would be a profound understatement. This is not a relic; it is the living architecture of what might be humanity’s most resilient political promise. It is a centuries-old handshake that has never been broken — not by war, not by revolution, not even by the tectonic shifts of empire itself.

A Siege, A Beginning: 1147

The roots of this alliance reach deeper than its 14th-century codification. During the Siege of Lisbon in 1147, English crusaders aided the nascent Portuguese kingdom in wresting its capital from Moorish control. This act of solidarity came more than 200 years before the formal treaties were written. In a medieval world where alliances were fragile, opportunistic, and transient, such early military and spiritual support seeded a trust that would crystallize into a perpetual pact.

Unlike many treaties, the Anglo-Portuguese accord was not born out of coercion, territorial division, or exhaustion after conflict. It emerged from a shared sense of purpose and complementary geopolitical interests. England sought an ally on the western flank of Europe; Portugal sought legitimacy and protection. It was mutualism before modern statecraft had a word for it

1373: The Perpetual Peace

On 16 June 1373, in the cloisters of London, King Edward III of England and King Ferdinand I of Portugal sealed what became known as the Anglo-Portuguese Treaty of 1373. Unlike most treaties of its era, it did not specify a fixed duration or limited scope. It declared a “perpetual friendships, unions, alliances and confederations” between the two nations.

Its language was extraordinary. It spoke not only of military aid but of “faith, truth and love,” anticipating modern notions of diplomatic partnership that transcend mere convenience. It articulated something resembling the DNA of trust — the idea that nations could bind their futures not merely through force or necessity, but through shared conviction.

1386: Windsor and the Architecture of Permanence

Thirteen years later, the Treaty of Windsor (1386) deepened this commitment. It was no longer just a promise of amity but an explicit defense pact: both nations pledged mutual assistance in the face of common enemies. The marriage between King John I of Portugal and Philippa of Lancaster, daughter of John of Gaunt, Duke of Lancaster, symbolized not just a diplomatic understanding but a dynastic intertwining of fates.

Windsor created a framework that outlived the medieval world. It became a strategic bedrock as the Age of Discovery unfolded, as the Atlantic replaced the Mediterranean as the axis of global power. While empires rose and fell, the Anglo-Portuguese alliance remained a quiet constant — less a headline than a foundation stone.

Not Just Allies, Co-Authors of History

Over the centuries, this alliance has been called upon at pivotal junctures. When Napoleon’s armies invaded Portugal in 1807, British forces rushed to its defense, transforming Lisbon into a critical strategic node of the Peninsular War. Portuguese troops, in turn, fought alongside the British in the trenches of the First World War.

In the Second World War, Portugal, under António de Oliveira Salazar, maintained neutrality but honored its ancient alliance when asked to allow Britain to use the Azores as a base — a move crucial to the Allies’ North Atlantic operations.

This was not the behavior of states locked in a legalistic arrangement. It was the reflex of trust forged through centuries.

A Treaty That Survived Empires

The endurance of this pact is staggering when contextualized. When the Treaty of Windsor was signed, the Ming dynasty ruled China, the Ottoman Empire was in its infancy, and the concept of the United States lay more than three centuries in the future. Since then, both countries have experienced monarchy and republic, empire and post-empire, industrial revolution and digital transformation.

Most alliances decay when their founding conditions fade. The Anglo-Portuguese alliance adapted. It endured the age of sails, survived colonial divergence, reconciled over global power asymmetries, and reemerged as a subtle, modern partnership within NATO and the European diplomatic order.

Why It Matters Now

To the casual observer, the treaty might appear symbolic today — a dusty document in an archive. But to scholars and diplomats, it embodies a rare principle: that peace and partnership can be engineered not only through power, but through durability, respect, and shared strategic imagination.

In the 21st century, where alliances are often transactional and brittle, the Anglo-Portuguese example offers a counterpoint. It shows that an alliance need not be loud to be powerful, nor temporary to be relevant. Its greatest achievement may not be any single battle won or crisis defused, but the unbroken continuity of trust across 650 years.

A Philosophical Reflection: More Than a Treaty

Perhaps the true significance of this alliance transcends even diplomacy. It speaks to the human capacity to build enduring structures — agreements that behave less like legal contracts and more like living organisms. Like an ancient oak, the Anglo-Portuguese alliance has grown through storms, pruning, and regeneration, yet never uprooted.

For historians, it is the longest continuous diplomatic relationship. For political scientists, it is a model of strategic resilience. But for philosophers, it is something greater: a testament to the idea that peace, when patiently cultivated, can outlive the wars it was meant to prevent.

The Scepter and the Pen

In 1147, it began with swords at Lisbon’s walls. In 1373, it was ink on parchment. In 1386, it was royal marriage. Today, it is trust quietly embedded in defense frameworks, economic cooperation, and diplomatic alignment.

Empires have perished, wars have burned continents, ideologies have risen and fallen — but this alliance, like a well-made bridge, still spans the centuries.

And perhaps this is what makes it far, far greater than a treaty.

It is not merely the world’s oldest alliance.

It is the living proof that peace — once forged with sincerity — can become the most enduring architecture of all.

You May also like

By Samantha Stafford

By Rojina Bohara