Enduring Or Bound To Be Broken?

By Carolina Berghinz

15th June 2025 Time 09:10

On May 14th, 2025, in a hushed and expectant room at Christie’s in New York, history tilted just slightly. Marlene Dumas’s painting Miss January was sold for a staggering $13.6 million, setting a new record for a living female artist. Yet amid the applause and headlines, a deeper question pulsed beneath the surface: Is this a singular triumph, or is the long-standing gender barrier in the art world—finally—on the verge of being shattered?

Because Dumas is not just an artist. She is a mirror of womanhood, a cartographer of human emotion, and a powerful emblem for every woman who has ever felt looked at, judged, unseen, or misunderstood. And her art? It doesn’t whisper. It dares.

Photo Credit: Christie’s

Photo Credit: Christie’s

From Apartheid to Art World Ascendancy

Born in 1953 in Cape Town, South Africa, under the choking weight of apartheid, Marlene Dumas grew up in a world fragmented by injustice and silence. The segregationist regime shaped much of her early worldview—and later, her resistance to it. In a system where skin colour governed destiny, and women’s bodies were objects for control, Dumas would soon learn to make art that fought back.

As a child, she collected photographs. Not just pretty pictures, but emotional evidence: magazine clippings, newspaper snapshots, faces of strangers, political martyrs, movie stars, and blurred women blinking into the lens of history. It wasn’t merely scrapbooking—it was a profound act of observation, a quiet rebellion against erasure.

She left South Africa to study in the Netherlands, where she would remain—carving out a creative space that fused feminine vulnerability with furious independence. From her earliest exhibitions, she rejected commercialism, refused the sexualised lens of the male gaze, and rebuffed institutions that demanded she dilute her style or soften her voice.

And while many women artists were coaxed into the polite fringes of minimalism, Dumas chose instead to explore bold, raw, psychologically searing figurative works. Her pieces weren’t safe—they bled emotion. She painted terrorists, porn stars, saints, children, corpses, and lovers with the same merciless honesty.

Her life and work formed a posture of refusal—refusal to be consumed, refusal to conform, refusal to commodify femininity on anyone else’s terms.

Miss January: Not Just a Painting, but a Reckoning

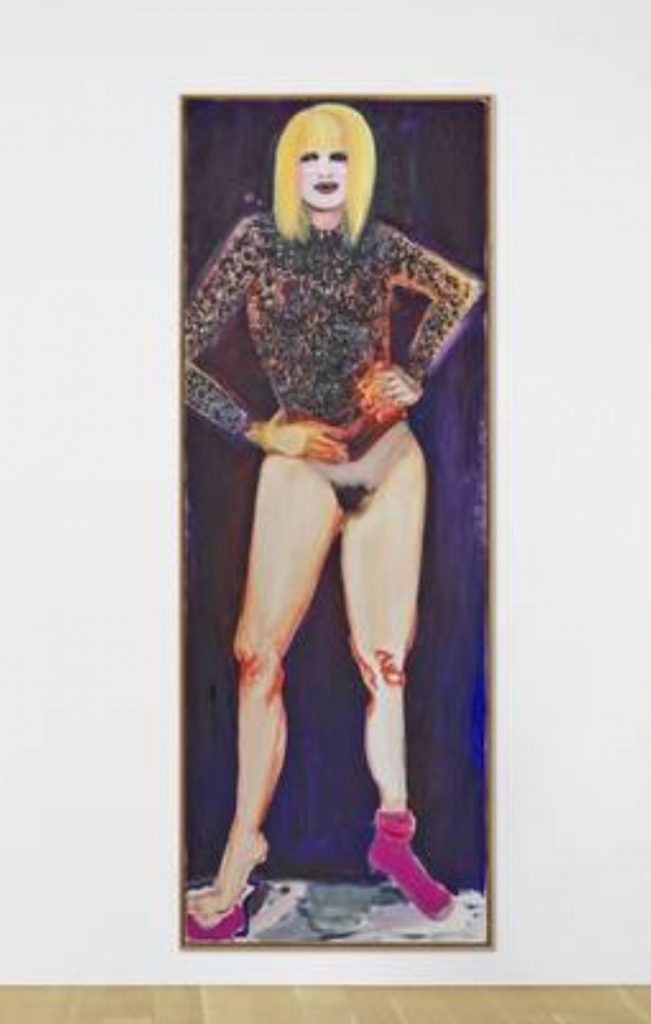

Miss January is more than 2.8 metres of canvas—it’s a storm. A blonde woman stares defiantly from the frame, clad in a semi-transparent blouse, nude from the waist down, one leg clad in a single, blood-red sock. She is not offering herself—she is daring you to interpret her.

Painted in 1997, the work reclaims and subverts the language of eroticism. The subject is at once passive and powerful, still yet charged, beautiful yet confronting. And now, in 2025, it has become the most expensive work sold by a living female artist—a fitting irony for an artist who never painted to be palatable.

Dumas’s muse in Miss January is not Miss Universe—but the very opposite: a woman whose body, stare, and context challenge the viewer to reckon with their own projections. The piece is monumental not just in scale but in meaning. It reclaims the canvas as a battlefield, and the female figure as its heroine.

An Icon for Every Woman Who Refused to be Framed

In a world where male artists still dominate the top auction blocks (Jeff Koons’ Rabbit sold for $91.1 million, and David Hockney’s Portrait of an Artist reached $90.3 million), Dumas’s success is still an exception—not yet the rule. But she represents more than a record price—she represents a social shift.

Just as Carmen Dell’Orefice models into her 90s, just as Princess Anne reinvents royal relevance in her 70s, Marlene Dumas embodies the endurance and evolution of the female creative spirit.

She is the anti-muse. The woman who paints, not to please, but to unearth.

Women across the world—whether scientists, teachers, artists, or activists—are often forced to perform femininity within tight, punishing frames. Dumas annihilates that frame. She paints the contradictions: beauty and decay, eroticism and violence, the soul and the body unfiltered.

Art as Emancipation, Not Decoration

Dumas has long said that “painting is about the human trace.” In her hands, it becomes also about the female space—that intimate, feral, uncertain territory of being seen, misunderstood, and finally, claimed.

Her use of colour is instinctive, her compositions emotional, her source material ethically explosive. She draws not only from photos of Patti Smith or Che Guevara shirts, but kidnapped Russian girls, martyrdom, mass media, and personal trauma. Her process is less performance than purification—she does not paint to preserve beauty, but to exorcise pain, and to interrogate power.

Like the surrealist Remedios Varo, whose Revelación (El Relojero) just sold for $6.21 million, and like Jenny Saville, whose raw self-portraits challenged beauty norms, Dumas belongs to a pantheon of women who make art not just as expression, but as liberation.

Enduring… and Breaking Through

So—is the gender barrier in art enduring, or bound to be broken?

With Miss January, the crack has deepened. A new generation of women are not just entering museums—they’re rewriting what deserves to be there.

And Marlene Dumas is leading that charge.

Not by posing, or pleasing, or persuading—but by painting exactly what the world wasn’t ready to see.

Until now.

You May also like

Anne Lipscomb – Editor in Chief’s “Pick of the Year”

By Rose Polpi

By Antonio Rocca,